A IIIF Concordance

As IIIF Manifests increasingly contain transcription annotations, the tools that are able to handle these documents must also treat text content as a first-class citizen. In our TPEN software, users regularly generate new annotations with text content that is included in the manifest documents made available for every project. In addition, TPEN allows for the easy inclusion of split-screen tools in the transcription interface, so I often spend some time experimenting with possible tools that assist in transcription, connect resources, or generate useful visualizations.

Welcome the Kaminski Handwriting Collection

Several months ago, OngCDH opened a conversation with the Kaminski Handwriting Collection, where David Kaminski has been working to capture samples of handwriting from all over, noticing that American Paleography is not formally studied with significant scholarly focus. Kaminski has been customizing TPEN in support of American Paleography and contributing code back to our software development. Recently, an effort by Ethan Kaminski caught my eye.

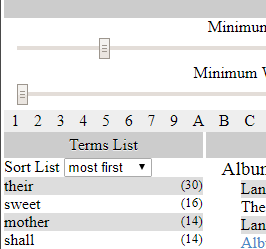

The visualization loads a TPEN project, analyzes the text content, and creates a concordance of the words transcribed, along with a count of occurrences. For the purposes of paleography, this tool would help find and compare popular words and letterforms throughout a document or collection. As a split screen tool in TPEN, it would illuminate common phrases and serve as a simple search-style tool.

As an experiment, I first changed the “projectID” lookup to harvest any IIIF Manifest URI, so the tool would be useful for any published documents. This included support for fetching resources that aren’t included in the original document—a best practice for AnnotationList objects used in the Presentation 2.x API. Once the tool was able to do that, I set my sites on the other connected information available to the interface.

Filtering the collection by the length of the word and its frequency seemed like an obvious place to start. Combined with standard ascending/descending sorting, a user could jump past stop words or focus on interesting cases without any configuration.

More usefulness was added by adding links to scroll the main page of entries to the selected word and adding theoccurrences count to each entry. Without spending some less experimental time, capitalizing on the availability of each annotation’s target to show the image fragments or provide links to the line specifically within applications like TPEN or Mirador will have to wait. Honestly, without specific use cases, I don’t have a lot of energy behind any case beyond integration into TPEN, but I am grateful to the Kaminskis for contributing momentum to both TPEN software development and the study of American paleography.

Challenges to overcome

There are standards that guide the creation and distribution of complex objects, like collections of books’ and manuscripts’ images; encoded transcriptions, translations, and commentary; and the annotations that are designed to link them together. Even if the paleography community across domains had established common conventions for combining these standards, covering cases even as narrow as transcriptions and translations introduce all sorts of inconsistencies. (Bryan Haberberger has covered many of these challenges in another post.) Supporting only TPEN manifests means IIIF Presentation 2.1.1 and expecting text content to always be in manifest.sequences[0].canvases[n].otherContent[0].resources[n].resource["cnt:chars"], which makes a lot of assumptions. Looking to a transcribed Stanford manuscript, the AnnotationList must be resolved first and then the characters are in resource.chars instead. In other manifests, text is a linked TEI-XML resource, covering the entire document, or transcription services supply page-at-a-time text, as FromThePage does. All this is just trying to find the text content before dealing with the fact that the text itself may contain partial XML markup and uses character sets, notation conventions, and languages that escape the most conveniently available regex snippets for tokenizing modern texts.

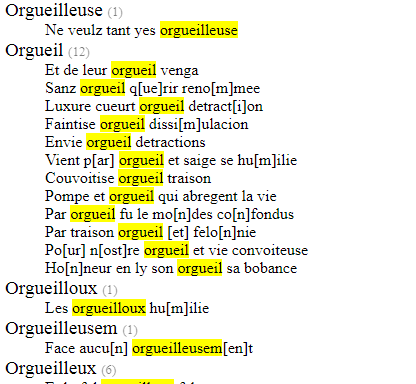

Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 6221, Provided by the Stanford University Libraries illustrates how nearly equivalent terms are not normalized and how notation conventions can complicate the analysis.

New Opportunities

There is absolutely no shortage of tools for word frequency and concordances. However, these tools all expect a level of preparation or access that is far from universal. It works well for focused projects, but few people have datasets that they can use for a quick look at an interesting visualization. On the other hand, IIIF Manifests are proliferating and, for all their capriciousness, tend towards conformance. Moreover, the data within Web Annotations on Canvases includes image fragments and other bits of information that is truly interesting to researchers and their robots. Considered briefly, I would categorize the next possible steps thus:

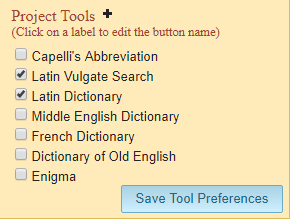

- Integration—the use of this tool within TPEN is simple with the split screen iframe configuration. The standard Capelli tool (git) is a standalone application that just works. For the specific purposes of TPEN, integration could be improved to link back to specific project pages, for example. Other forks may also be established for connections within other web applications.

- Visualization—in the digital humanities, the most boring datasets are often gilded with impressive word clouds, dynamic graphs that jostle under your cursor, and science-y distributions that turn conclusions into PowerPoint kibble. While I would resist piling these on without a use case, web applications like Voyant Tools have proven that flashy still attracts a lot of eyes (and it is customizable). In this same category, one would place UX/UI improvements, clarifying the analysis, providing better filtering and searching, etc.

- Investigation—Each line of results has an annotation associated with it that links to image fragments, Canvases with metadata, and Manifest documents. A summary page of “orgueil” may show all 12 instances in the original texts for comparison. A “bookbag” may allow users to hold onto a few lines to compare against another text. Most importantly, as a standard document format, a user could follow a link out of the application to transcribe this document in TPEN, view the manuscript in Mirador, or export the results in a format expected by a more comprehensive, albeit picky, analysis application on or offline.

This is happening

There is a 99% chance that this tool is handy enough that I will throw a few more days against it to integrate it with TPEN. A new post here will announce its inclusion on the default tools set and users will be oblivious to it. After awhile, I may combine several public transcriptions together and release a supercut output of existing transcriptions. At that point, we’ll pretend it is brand new and present it in a community call or at a conference and amaze scholars who will now clamor to sign up.

Of course, it would be even nicer if there were specific use cases beyond our tool that could help establish a motivating roadmap for development. The code for this is in fact so simple that many may simply be moved to contribute in a small way. Please drop an issue explaining your use case or feature request; appreciate that the code has no dependencies and requires no building or compiling and contribute; try out a sample; or add your own manifest parameter to https://cubap.github.io/IIIF-concordance/ and see if your favorite document chooches and Pinstatweet it!